Constructed Portraits: Make Her More Beautiful

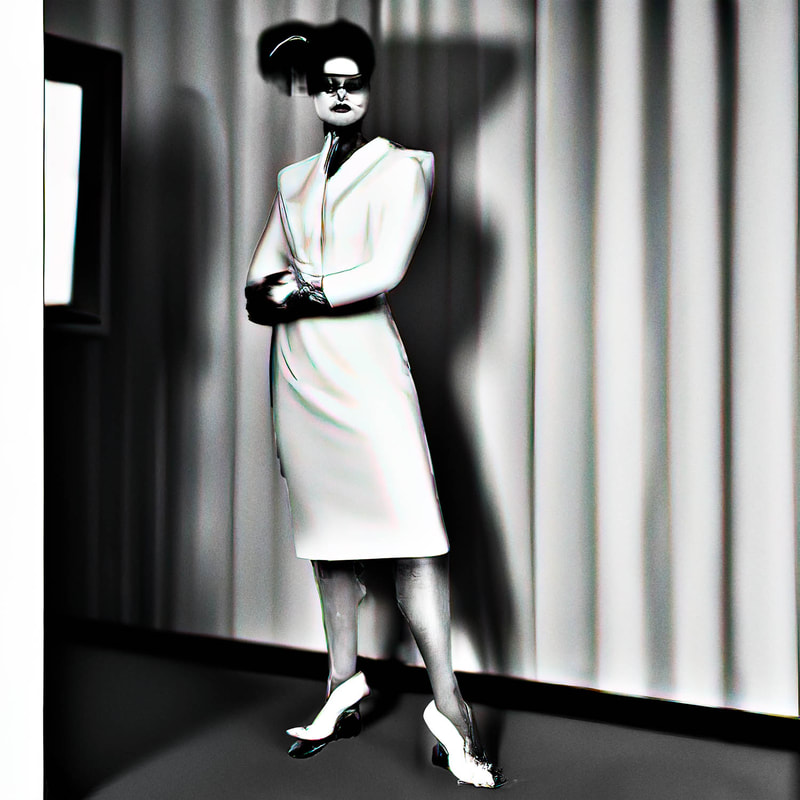

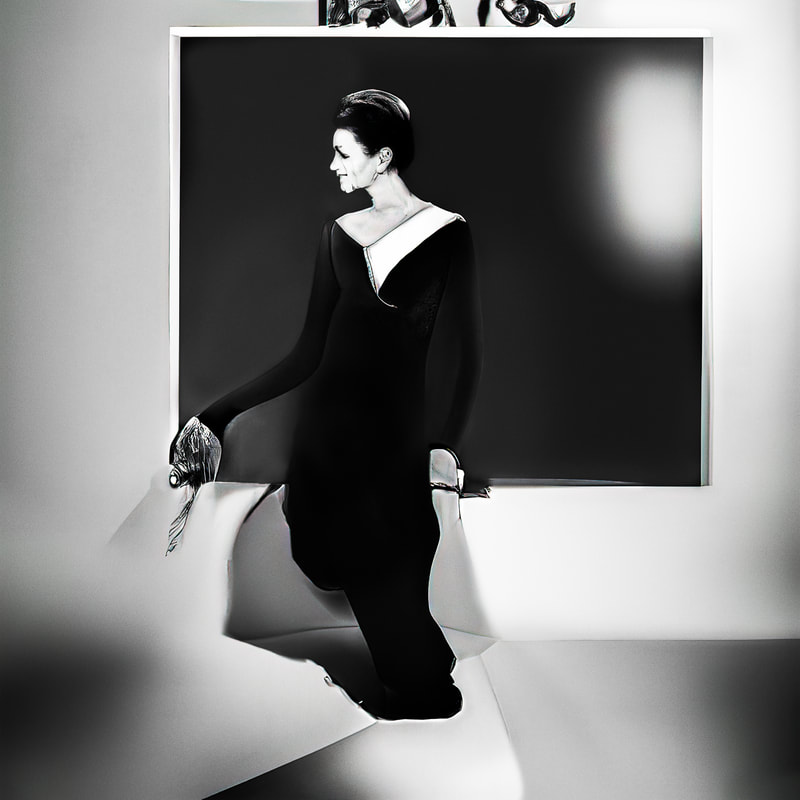

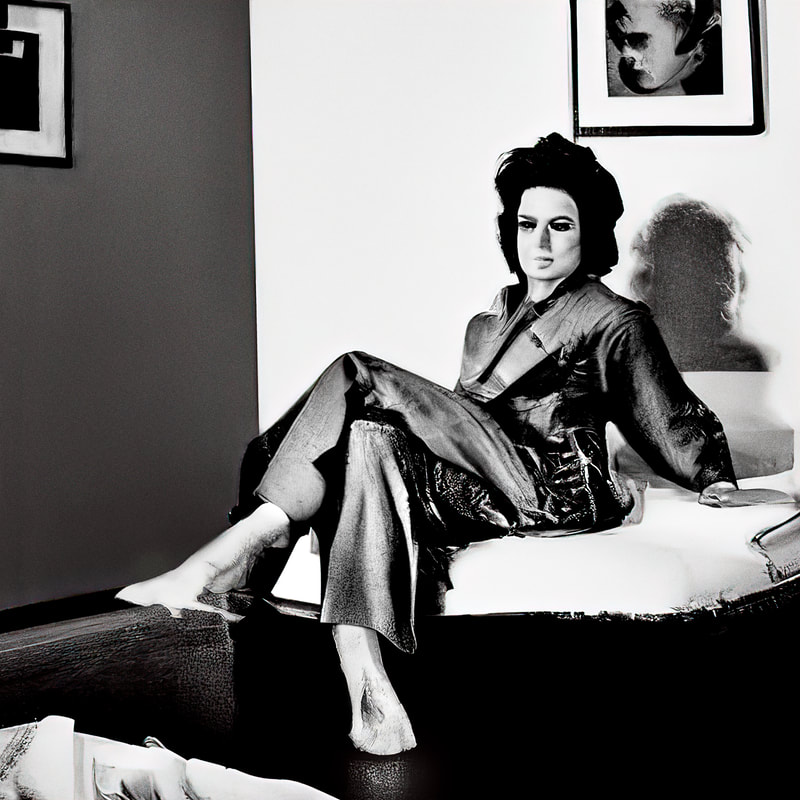

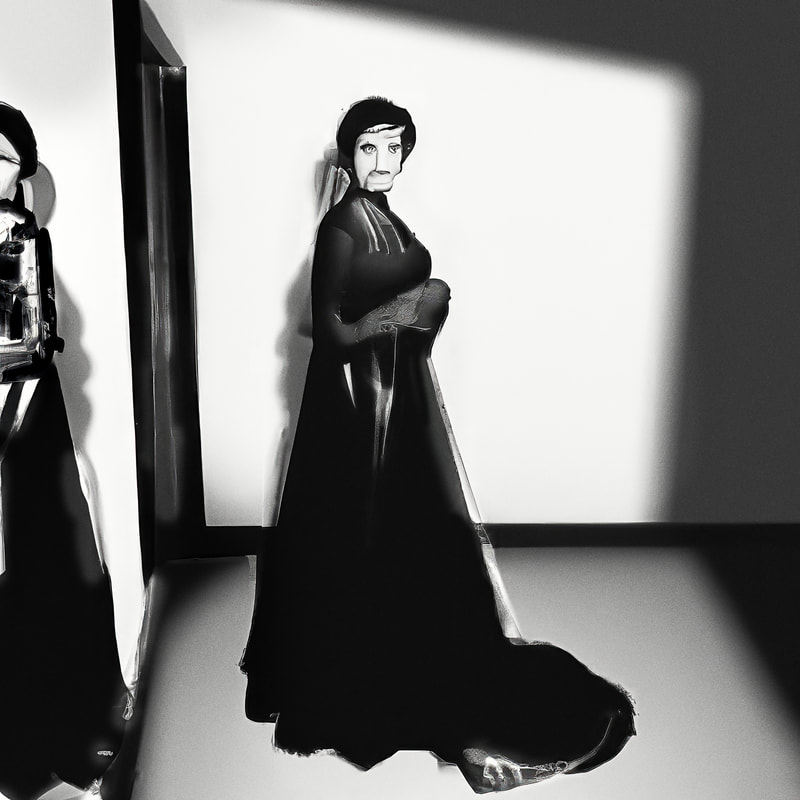

Constructed Portraits: Make Her More Beautiful is created using an archive of photographic negatives of women, fed into an AI model with the prompt to "make her more beautiful." The female-presenting figure is then collaged, patched, and reassembled to examine the optics of representation and interrogate societal beauty standards.

What distinguishes this work is the integration of cutting-edge technology with painstaking craft. Each image requires hundreds of hours of hand work to apply color, shade, and tone, followed by an exhaustive pigment printing process. Analog and traditional printmaking techniques bring this technologically advanced work to a level of material refinement that could only be achieved through sustained hand labor.

The contrast between the real and the invented is intentionally unsettling. The depicted subjects appear aware of being photographed, yet neither the person nor the moment is truly preserved. They are constructed and altered to such an extent that the figure loses connection to the fragments from which she was made. This work taps into anxieties surrounding AI in art, exposing deep-rooted assumptions about photographic truth and the pervasive fear that machines will replace human creativity.

Constructed Portraits was acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and included in the exhibition Digital Witness: Revolutions in Design, Photography, and Film.

All works are archival pigment prints, 31 × 31 inches.

Lior, 2024

Noy, 2024

Vicky, 2022

Einav, 2024

Mira, 2022

Yvette, 2023

Ella, 2023

Golda, 2024

Donna, 2022

Anya, 2023

Isabella, 2022

Roni, 2023

Roxy, 2022

Dvora, 2023

Natasha, 2022

Esmerelda, 2022

Inge, 2023

Yuval, 2024